PunchClock

Spring 2016

Improving the office experience by helping coworkers communicate better.

The Problem

From: Jackie

Date: Thursday, January 7, 2016 at 11:18 AM

To: Niko

Cc: Mktg Creative Campaign Team

Subject: Re: Re: Re: WFH Thursday

I’m not feeling well so I’m heading home to work for the remainder of the day.

Jackie

> From: Kasey

> Date: Thursday, January 7, 2016 at 9:15 AM

> To: Niko Simonson

> Cc: Mktg Creative Campaign Team

> Subject: Re: Re: WFH Thursday

>

> Working remote.

>

>> From: Niko

>> Date: Wednesday, January 6, 2016 at 1:04 PM

>> To: Mktg Creative Campaign Team

>> Subject: WFH Thursday

>>

>> Hey Team,

>>

>> I’ll be working from home tomorrow, offline from 11:30–1:30 to go to the dentist.

>>

>> Thanks,

>> Niko

Is your team’s schedule an endless string of Re:s and Fw:s that looks like a chain letter from your great aunt?

Who’s working at home? Who’s out on vacation? Who’s here, but hiding in the supply closet? True story, I came back from vacation to find that over half my emails were daily schedule updates. I often see heads popping up like gophers as folks scan the room to see if a colleague is at his or her desk. In a large office, trying to keep everyone’s status straight is impossible. There has to be a better way.

Most of the time I don’t need to track who’s going to be away later in the week; what I really want to know is whether or not they are available right now. If I walk up to their desk, will they be there? Or should I email them? How can we more clearly and efficiently communicate our immediate out-of-office plans?

Inspiration

A while back, I read a brilliant post by UK-based design studio, 383, on Building a Connected Studio. They had used their own expertise to build an entire smart-office system to make their team’s life easier and showcase the studio’s abilities. This included a custom API, a better guest check-in, connected meeting rooms, and, most interesting to me, a “who’s in the studio” app and Arduino-powered display board.

I was already familiar with Arduino from a project I had done at home, but I had so many questions, specifically, lights. How are there so many!? Thank god for the Twitter:

A few Britishly witty tweets later, I knew I had found what I was looking for.

I wanted a way to integrate what I knew about building apps and how to create a service across multiple platforms. This would let me do just that: For the app to be universally accessible, we’d need a web app. If we wanted to harness native mobile features like tracking location to automatically check someone in, we’d need a mobile app. And if we wanted to make sure everyone could see the information they needed and stop relying on their damn email, we’d need a big ol’ light-up board.

Design

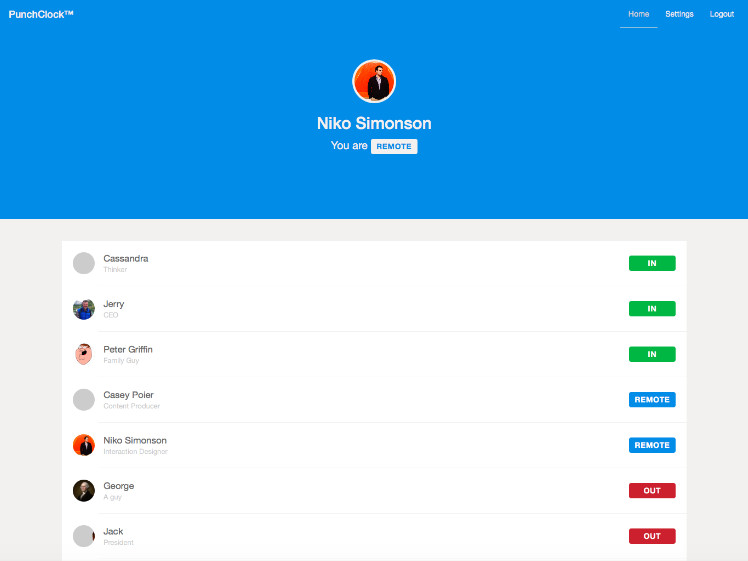

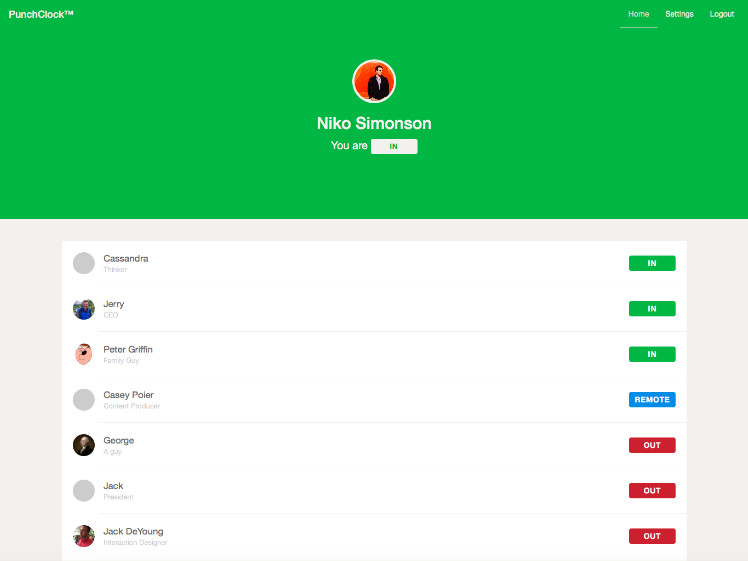

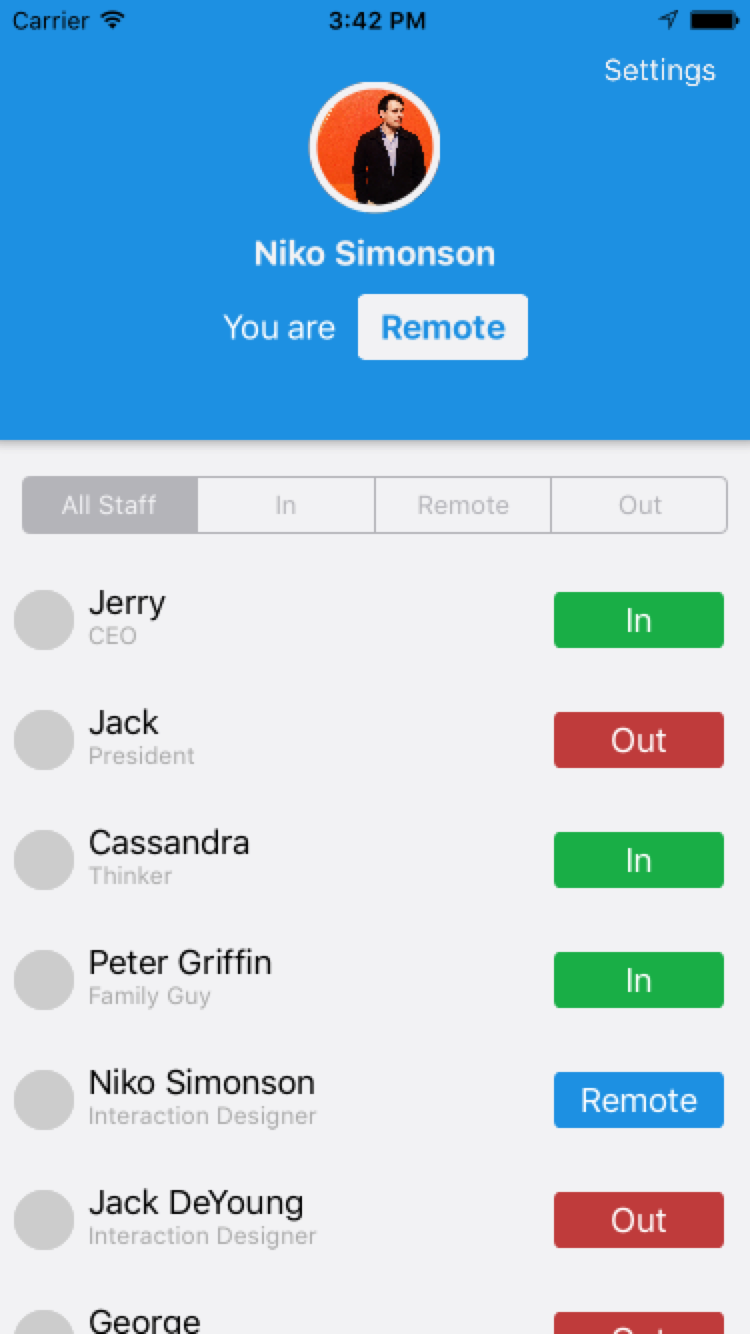

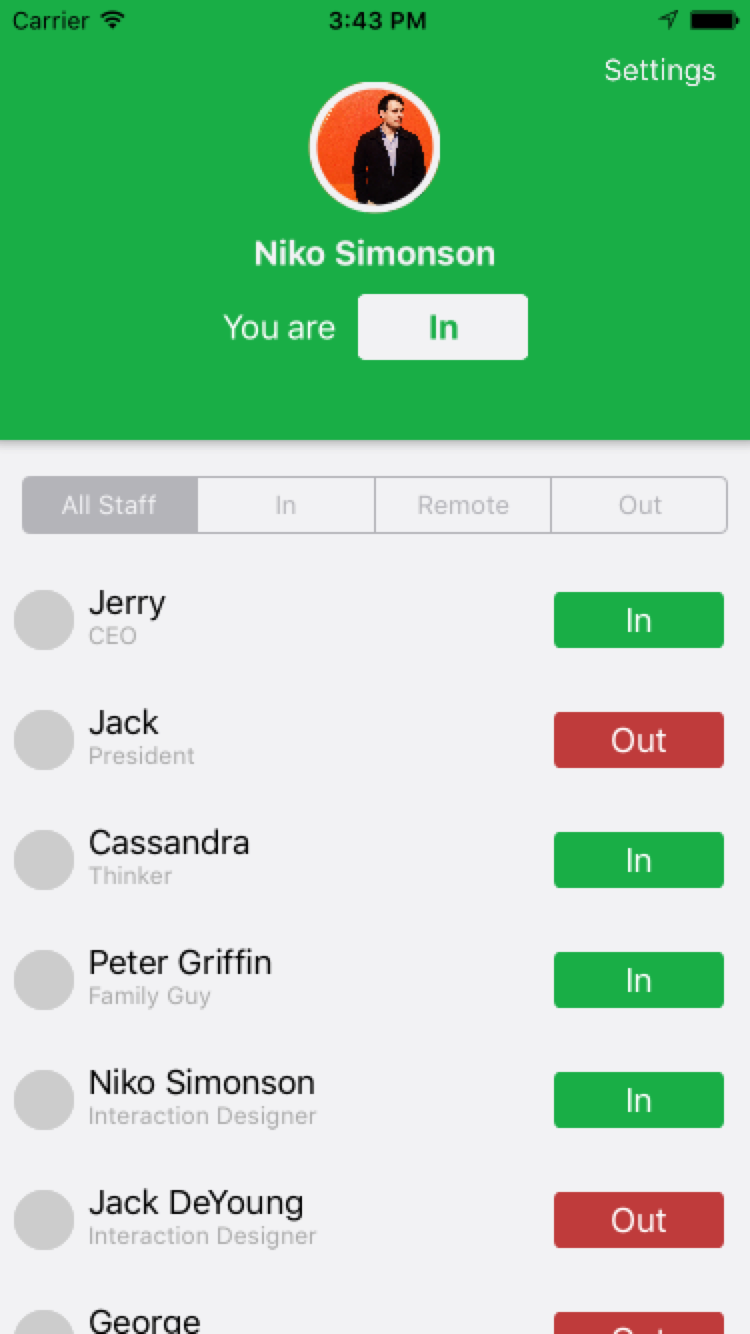

The app designs would be simple. A user only needed to do one of two things:

- Change their status.

- Check other people’s statuses.

No need for chat features or away messages. Just the facts.

I knew I would be building a native app to go along with the web app, and I wanted the experiences to be as close as possible. I could recreate the all powerful UITableView from iOS in HTML, and I limited the number of statuses to three: In, Out, and Remote. (I considered adding a “Busy” status and linking it to our calendar system, but I know some folks on my team have more meetings than hours in a day and would always appear to be busy.)

So, with my minimal design sketched out, I jumped straight into coding a working prototype. I didn’t see any sense in adding a pretty wrapper if I couldn’t get it working.

The Part For Nerds

The first thing I had to do was sketch out the architecture. How was everything going to work together and talk to everything else?

I had been playing around with a Facebook JavaScript library called React. It is essentially the view in a model-view-controller pattern and excels at fast real-time updates and one-direction data flow. This library, along with their architecture pattern called Flux, was really something I wanted to explore in depth. While it may have been slightly overkill for this project, I got some good practice learning new software patterns and the benefits and limitations of a library like this one.

That was that for the web app, but I needed to build the companion iOS app. I’d been learning a lot about Swift and the iOS SDK and knew that this would be pretty straightforward. The only thing I was missing was a way to keep all the data synced across devices.

I had recently been introduced to an easy-to-set-up, real-time database called Firebase. Its library bakes in all the functionality across a dozen languages. And the schema automatically become endpoints in a simple API. No need to write backend code.

The physical board would be powered by an Arduino that would control a string of LEDs. Arduino are great at turning things on and off and can double as a basic web server. I initially tried to get the data directly from Firebase, but memory management on an Arduino can be a challenge. I quickly learned about the unpredictable havoc memory overflow can wreak.

In order to compensate for this, I needed the Arduino to only receive everyone’s status in a presorted array. This required me to set up a proxy server on Heroku that, when polled by the Arduino, would request the latest and greatest from Firebase and return it all in a pretty package. This way the status lights could be easily added and removed without updating the Arduino’s firmware.

The Result

To date the apps are nearly finished and the string of lights is lighting up like a Christmas tree. The holiday season forced us to focus on project work, so the lights still need to be mounted on the board and hung on the wall. We’re planning to have a handful of folks on the team test it out and see if we’re on to something. At the very least maybe it’ll clean up my inbox. Stay tuned.

Update: I since took a job with Substantial, a design and development agency, and put this project on pause for the foreseeable future.